WristRotate is a personalized motion gesture delimiter that allows to accurately separate involuntary motion from gesture input. Through an extensive data collection and analysis, we were able to identify a gesture that (1) is uncommon in daily life; (2) quick and easy to execute and (3) easily and reliably detectable. The gesture is executed by simply rotating the lower arm and wrist outwards and back inwards twice. We implemented a gesture recognition system based on Dynamic Time Warping to partition a stream of accelerometer readings to identify possible gestures and to classify them accordingly. In our data acquisition phase, we collected 435.1 hours of smartwatch acceleration data during everyday usage in which the WristRotate gesture has only been found twice.

Introduction

With the current rise of smartwatches and fitness tracking armbands an increasing amount of people are wearing an always listening collection of motion sensors on their wrists. While smartwatches often allow for sophisticated input, these are not always appropriate (e.g. speech input) or not always possible (e.g. touch input requires the opposite hand). Fitness tracking bands such as the fitbit on the other hand often do not have such sophisticated input techniques. Still those devices can be used for input as they often have a steady connection to the user’s smartphone. We envision a gesture based interaction design that allows for inconspicuous and one-handed interaction. In comparison to for example speech input, such motion-based gestures are perceived as more socially acceptable.

But the crucial factors towards a high user acceptance of such a motion-gesture based system are high reliability and high recognition rates with low rates of false-positives. Compared to interaction with smartphones, this is an even bigger problem for wrist-worn devices. While smartphones rest in our pockets for the majority of time, these devices are bound to our arms meaning that they will be in nearly constant motion. Especially as we do complex motions with our arms during a day, these could easily be misinterpreted as a gesture (the so-called Midas touch problem). For the interpretation of gestures based on internal sensors are variety of different techniques exist. But those are not designed to cope with the steady movement of our wrists and often include the need to press a button for activation of the actual recognition. Therefore, they are not suited on its own. To avoid this, an effective and easy-to-use delimiter to separate involuntary motion from gesture input is needed. Afterwards, the aforementioned gesture interpreter can be easily applied.

Design of Wristrotate

As already outlined, we aim on supporting not only wrist-worn devices with sophisticated input possibilities such as smartwatches that offer a touchscreen or at least some buttons. Since other devices like fitness tracking bands do not offer such input possibilities, we cannot rely on them for interacting. Another reason for not relying on them, lies in the fact that they require interactions of the opposite hand for activating (OSI). As we also want to support interactions on the go, we favor same-side interactions (SSI). For example, this opens up the possibility to carry something in one hand while interacting with the wrist-worn device worn on the other hand. As a consequence, we focus on the use of information we can get from the motion sensors, i.e. to detect a special gesture we can use as delimiter to distinguish between involuntary and intended interactions.

We defined a set of requirements that should be met by our delimiter gesture:

- The gesture should not be involuntarily invoked during everyday life.

- The gesture should not require large or complicated movements of the arm or wrist.

- The gesture should be easy to remember and quick to perform.

- The gesture should be reliably detectable when done on purpose.

- The gesture should not interfere with gestures that are typically used in other applications.

Compared to the set of possible gestures that can be executed with a smartphone in the user’s hand, the set of possible gestures for a wrist-worn device is already limited. Our set of requirements stated above further reduces the available gestures. We have to dismiss gestures that are complex (either regarding their length or their required movements) as well as those that are typically used in already existing applications (e.g. turning one’s wrist towards the user to activate an Android based smartwatch). Furthermore, we have to exclude all interactions that often happen involuntarily during everyday life to avoid a high number of false positives.

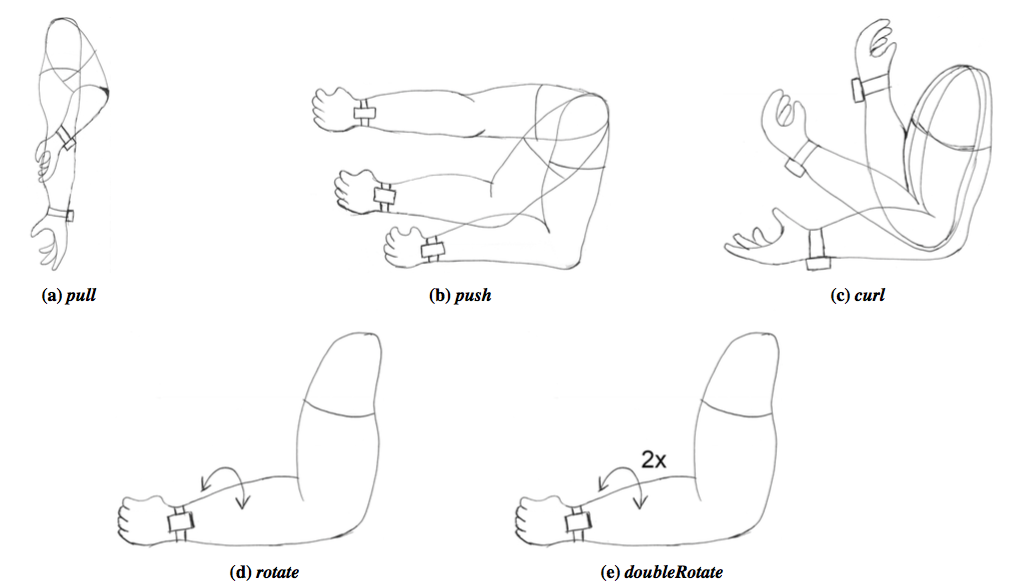

In the end, we identified five gestures for further examination :

- (a) a pull gesture for which the arm is hanging parallel to the body and is then pulled towards the shoulder (pull).

- (b) a push gesture where the arm is held parallel to the ground and pushed forward like a punch (push)

- (c) a gesture where the arm is first stretched out (palm facing upwards) and then the lower arm is bend towards the shoulder similar to a bicep curl (curl)

- (d) an outwards rotation of the lower arm and wrist, quickly followed by a rotation back inwards (rotate)

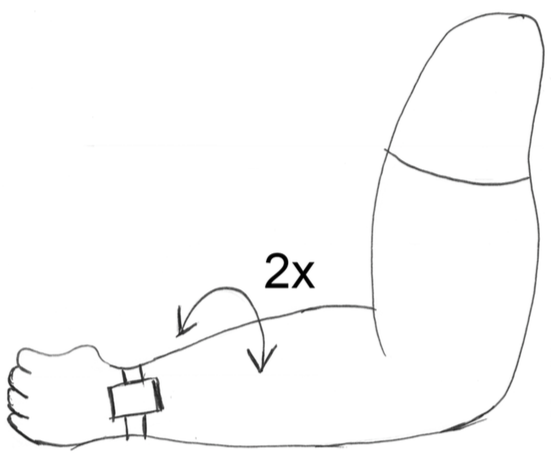

- (e) an outwards rotation of the lower arm and wrist, quickly followed by a rotation back inwards, executed twice in a row (doubleRotate)

Gesture Recognition System

Our gesture recognition approach is based on accelerometer readings from a Pebble smartwatch. The raw three-axis accelerometer data from the smartwatch includes noise and gravity, i.e. when the accelerometer is at rest, the only force that is affecting the sensor is the Earth’s gravity. To transfer these raw values into linear acceleration values reflecting the pure motion of the wrist, we applied a combination of a low-pass and a high-pass filter.

To identify potential gestures in the continuous sensor data stream, we use an algorithm which detects the start and stop points of gestures in a continuous time series and thereby partitions the stream into segments. Only those segments that are considered to contain a gesture have to be further examined by our classifier. The algorithm is based on the assumption that the movement energy of the smartwatch increases over a certain threshold when a gesture starts and decreases below a specific threshold when the gesture ends.

To compute the start and end points of a potential gesture, we utilize a sliding window approach with a window size of N = 5. As we sample our data with a frequency of 50 Hz, this corresponds to a window length of 100 ms. To reduce noise, we use an approach with two overlapping windows. We calculate the average energy level for each window and consider a window as starting point for a gesture if the calculated energy level exceeds a specific value. We regard a gesture as complete when the average energy level drops below a small value again. We empirically chose an average energy level of 70 and 5 respectively.

The segmentation process described above provides potential gestures that afterwards need to be checked for the specified delimiter gesture. For our classification, we utilize Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) – a technique well-known from the field of speech recognition but also widely used in other areas for recognizing patterns in continuous data streams. DTW measures the similarity between two time sequences of different time series which may vary in time or speed. To be more precise, the algorithm tries to calculate an optimal match between the two given time sequences by warping them non-linearly in the time dimension and figuring out the costs to match them. The so-called warp distance can be used to determine how similar a time sequence is to a given reference sequence. A warp distance of zero indicates that the two sequences are identical – the bigger the distance, the more different are the sequences.

Results

Overall, 7501 segments or potential gestures were found by our segmentation algorithm in the 435.1 hours of collected data. We recorded training data to be able to interpret these potential gestures. From the two sets we recorded for each of our gesture candidates, one set was used to train our Dynamic Time Warping based classifier. With the user-specifically trained classifier we then classified the potential gestures which were detected in the user’s corpus of motion sensor data during normal usage to be able to make a statement regarding the false-positive (FP) rate, i.e. the number of erroneously detected gestures in relation to the total number of examined gestures. The combined results for all participants can be seen in the following table.

| pull | push | curl | rotate | dblRotate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detections | 40 | 79 | 126 | 608 | 10 |

| FP rate in [%] | 0.53 | 1.05 | 1.68 | 8.11 | 0.13 |

| Avg. per hour | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 1.40 | 0.02 |

As can be seen from the results, the doubleRotate gesture performs best across all participants as only 10 occurrences were detected.

Discussion

Our analysis of the 435.1 hours of recorded daily motion data shows that three of our proposed delimiter gestures are only rarely detected during daily motion resulting in a low false-positive rate, i.e. it is in general not to expect that the chosen delimiter gesture would often be activated erroneously. Due to a significantly higher false-positive rate, the rotate gesture seems not to be a suitable choice for a motion gesture delimiter as it does not fulfill our first requirement to be not involuntarily invoked during everyday life. Instead the doubleRotate gesutre fullfills all of our requirements and has a low False-Positive rate in the analys of the recorded data.