When operating a mobile device one-handed the thumb is selecting objects on the touch-screen while the rest of the hand is concerned with holding the device. The current trend towards devices with increased screen-sizes of up to 6-inch makes it close to impossible to reach all parts of the screen for users with average thumb-size when operating the device one-handed. To overcome this problem current large-screen devices often offer adapted user interfaces for one-handed interaction. As these modes have to be triggered manually they induce a critical overhead.

In my Bachelor thesis I developed an algorithm that allows to determine the handedness of the user from their unlocking behaviour. Based on a k-nearest neighbour comparison of the internal sensors of the smartphone during the unlocking process, my algorithms correctly can distinguish, one- and two-handed usage as well left and right handed unlocking correctly in 98.35% of all cases.

Motivation

With the introduction of Apples iPhone, capacitive touch-screens became the de-facto standard input on mobile devices. Unlike earlier devices featuring different form-factors and layouts of hardware buttons, touch screens offer – compared to hardware buttons – a flexible layout of information and input. Yet, they also have several drawbacks. Besides the lack of proper tactile feedback, their main problem is that the screen and its desired size dictates the size and shape of the mobile device. This is even more amplified with the current trend towards devices with screen sizes of up to 6-inch (e.g., the Samsung Galaxy Note 4). Nonetheless, such screen sizes are becoming increasingly popular, the iPhone 6 has been sold over ten million times in the first three days and has a screen size of 4.7 inches. Operating them comfortably (i.e., reaching all parts of the screen) with one hand while keeping a firm grip is virtually impossible.

The problem is that – while holding the device with a steady grip – the thumb is supposed to select objects on the touch screen. This is unique to the interaction with touch screens and results in a physical overhead. However, with increased screen sizes, users with average hand-sizes are unable to reach all parts of the display comfortably, without changing the grip. Yet, the grip is known to have a significant effect on the performance of the user. For this reason, understanding the handedness of the user and number of hands involved in the interaction is crucial. Reaching the top left corner of a big device is impossible without adaptation. This comes at the cost of possibly dropping the device, and will likely affect interaction performance.

With the increase in screen size, manufacturers began to introduce user interface adaptations. For example, the iPhone 6 allows to temporarily shift down the user interface. This adaption, however, has several limitations: (1) half of the user interface is temporarily invisible; (2) after an action is performed, the adaptation has to be invoked again, potentially requiring many actions that are not directly related to the interaction itself – on the contrary, keeping the adaptation alive forces users to manually switch it off again; and (3) even with this generic adaptation, users are forced to slightly changing the grip of the device. Despite their limitations and potentially complicated manual process, these adaptations allow for maintaining known affordances.

To take these adaptations to the next level, I propose an algorithm that automatically detects whether the user is operating the device with one or two hands as well as with which hand the user holds the device. My algorithm is based on sensor data (here: accelerometer, device orientation, and touches) during the unlock procedure. It uses a k-nearest neighbour (kNN) comparison with a weighted dynamic time warping (DTW) as distance function. Based on minimal training sets (n = 5) for each of the hand conditions, my algorithm achieves an accuracy of 97.78% for a swipe to unlock, 98.51% for a pattern to unlock and 99.25% accuracy for a pin unlock. I believe that this would easily avoid having users to switch between left- and right-handed mode, e.g., for single-handed keyboards.

Concept

Before considering an adaptation of the user interface, it is of utmost importance to identify whether the user operates the device single-handedly or with two hands. An adaptation does not need to be performed when users operate the device with two hands, yet, when operating the device single-handedly, having knowledge of which hand is holding the device is crucial. Otherwise, the user experience will be diminished drastically. Knowing with which hand the user holds the device would avoid having users manually selecting the best adaptation of the user interface.

To allow for this, my algorithms collects several sensor readings during the unlocking process – accelerometer, device orientation, and touch points. It then compares this data to already recorded datasets where the handedness was known. For the classification I use kNN, a non-parametric classification method. The input consists of k training examples in the feature space; the output is a class membership. Thus, each new dataset is classified by a majority vote, where the dataset is being assigned to the class closest to k nearest neighbours of this class.

Naturally, for such a classification a distance function is needed. This function should consider that users take varying times to unlock their device. Thus, I first apply DTW to allow for comparable sensor data from unlocking procedures of different lengths. Originally, DTW was developed for speech recognition and is well-suited for comparing two time sequences of data. It looks for similarities between the sets and calculates the costs to match them. As a result DTW determines a distance – the warp distance – that can be used to determine how similar a set is to the reference set. A warp distance of zero indicates that the two sets are identical. Larger distances denote larger differences between the sets. I chose to use this warp distance as the distance function for my k-nearest neighbour comparison.

To gather the needed training sets, users can be asked to unlock their several times. That is, users are required to enter their pin or pattern several times using either their left hand, right hand or both hands. As multiple entries for patterns or pins are already commonplace on current devices, I believe that this would only induce a minimal overhead.

Unlock User Study

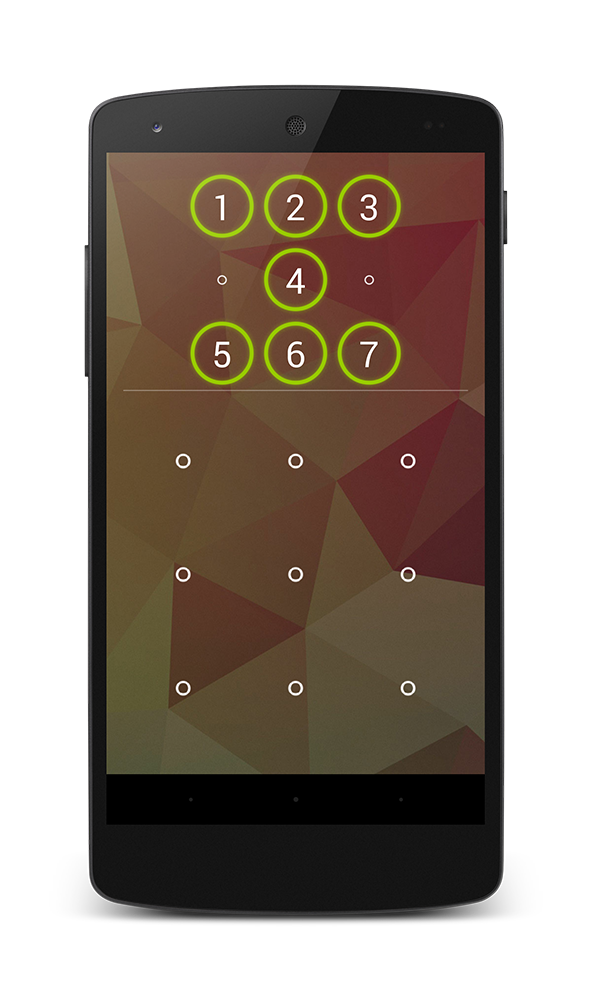

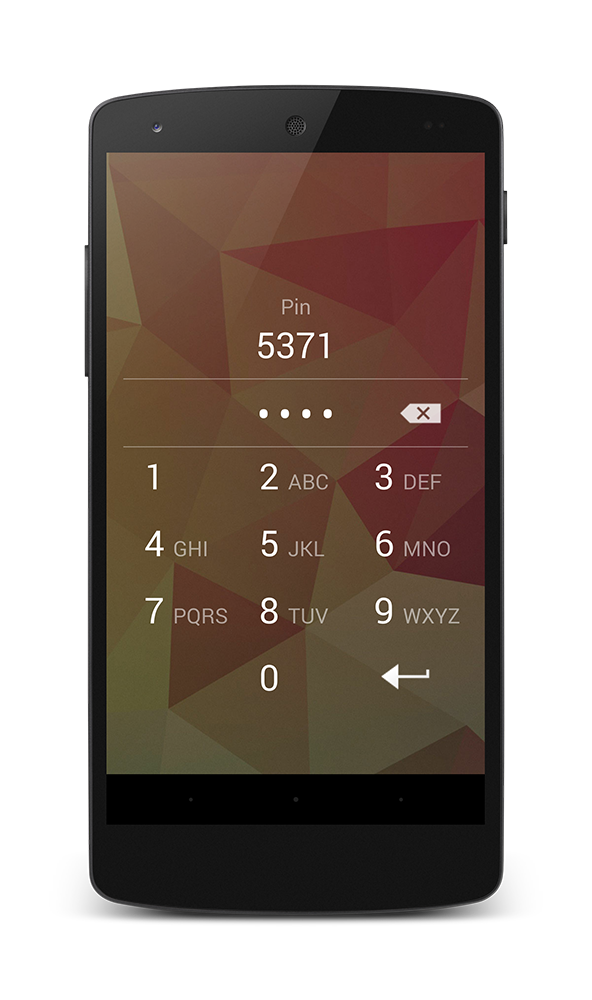

I implemented the aforementioned concept to test the suitability of this approach for handedness detection. As I consider collecting data while unlocking a mobile device, I developed three unlock applications that allow us to collect the sensor data that is needed. I did not intend to create artificial experiences, and thus extracted the original swipe-to-unlock, pattern, and pin unlock applications from the android open source project. These are also used in Google Nexus' roms. I did, however, modify the applications so that they save the touch positions (x and y positions and their the contact size), the accelerometer data and device orientation information. I recorded this data including timestamps from the moment the user first touches the device until it is unlocked. For the pin unlock application we added a field showing the pin code that the user is supposed to enter. Additionally, I added a small graphic showing the order of the pattern for the pattern unlock. To collect data we used a LG Google Nexus 5 as a reference device with a 5” screen reflecting current developments.

For each application I had three conditions: left-handed, right-handed and two-handed. For the two-handed condition I asked the participants to use their preferred hands for holding and touching the device. For the pin- and the pattern-unlock we had two sets pins and patterns. Each participant had to conduct 50 unlocks for each condition with each application (two times for pin and pattern unlock). This resulted in 750 trials per user: 3 conditions × 50 unlocks × 5 applications (swipe-to-unlock, pin1, pin2, pattern1 and pattern2). Users had the possibility to pause after each trial. Before the study, each participant was allowed to try each of the unlock applications five times. Overall, the study took approximately 15 minutes including the introduction phase.

I recruited 12 users (6 female) with an average age of 22.5 years. All of my participants were right handed and owned a smartphone with similar unlocking applications. The average screen-size of the participants devices was 4.3” and they all used one form of the unlocking applications (3 swipe-to- unlock, 4 pattern- and 4 pin unlock). For the two-handed interaction all participant except one would hold the device in their left hand and interact with the right hand. The users were asked to stand during the study. This was done to emulate a mobile user that stops to, e.g., look up directions.

Discussion

Across all three applications, I achieved an accuracy of 98.51%. From the non-correct classified trials only 6 trials (0.88%) were wrongly classified. Although these might lead to a worse user experience, I would argue that the benefit that could be reached through our algorithm is higher then the possible bad experience the user could face.

Besides the above described kNN classification approach, I also investigated the use of support vector machines. This did not result in better detection rates. I would recommend using kNN which comes at the advantage of being computationally rather inexpensive and thus can easily be integrated into existing mobile devices.

I acknowledge that the data I gathered was collected while standing and I did not cope for potential extra motion that might occur, e.g., by walking. Nevertheless, my initial evaluation of data collected by two users while walking showed that the motion-induced change on accelerometer data did in fact increase the distance towards the training sets (which was created while standing). Yet, the increase occured evenly in all classes. For this reason, I expect that there is no change in detection accuracy, which further outlines the advantage of the k-nearest neighbour approach compared to more advanced classifications.

User Interfaces

As an extension I developed serveral user interfaces which adapt to the handedness.

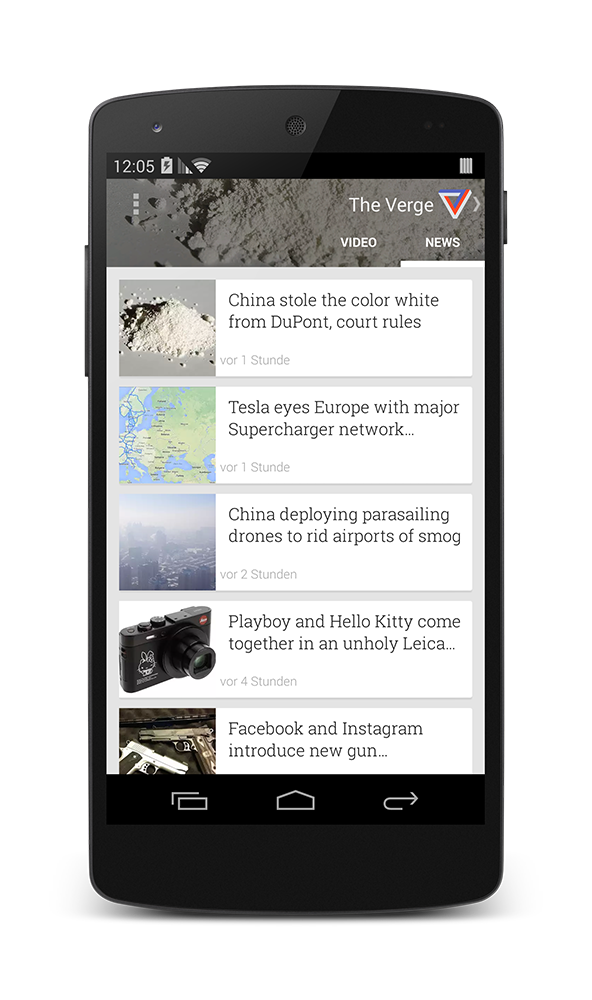

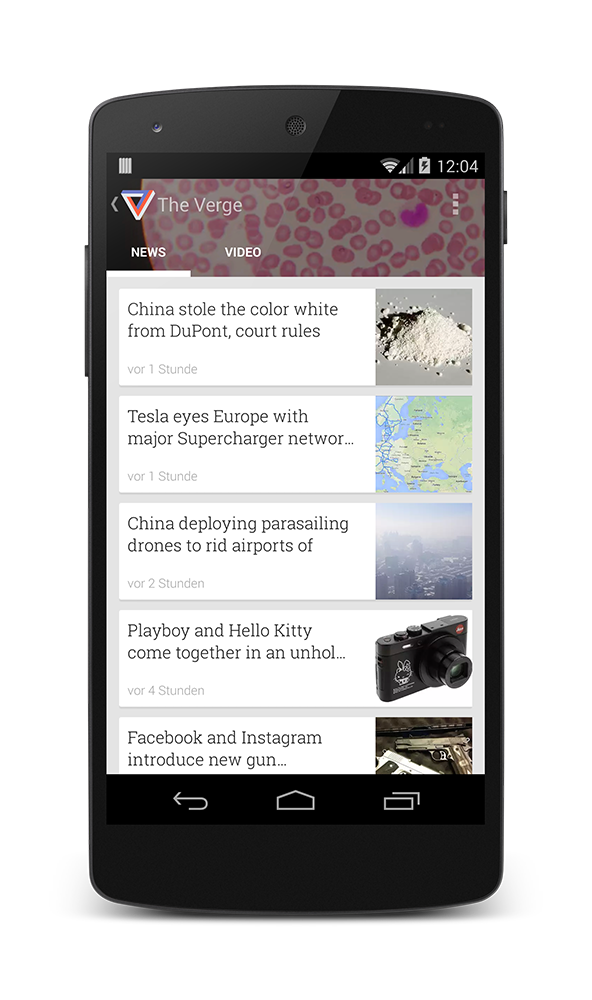

The first adaption is to mirror the complete interface. For instance, the Goolge Play Kiosk App displays the news title with a thumbnail right to it. This layout has an immense drawback for left handed interaction because the left thumb will be covering the tilte while scrolling. A simple solution would be mirroring the layout so that the thumbnail is placed left to the title.

Another adaption of the user interface would be a magnfification of the objects which are out of space of the thumb. The magnification causes a smaller distance between the object and the thumb and lighten the control.

A similar approch would be sliding the objects into the reachable area of the thumb. The distance will also be decreased but the interface have to masking some elements in the bottom area to slide the object out of the top area.

The last adaption would be a change in the resolution, so that the complete screen shrinks towards the thumb. This modification shorten the distance to the objects but the decrease in size could make it difficult to hit the objects.